Who are the Raga Nerds?

Raga Nerd is a sociological oversimplification, like “Yuppie,” “Hippie,” or “Feminist.” I’ve never known anyone who referred to him or herself in those terms, so perhaps the people I call Raga Nerds would also resist the label. Nevertheless, here are some characteristics I have in mind: If you were a prototypical Raga Nerd, Indian culture would be both familiar and alien, omnipresent in the home but unfamiliar to your peer group. You make trips back to “the homeland,” where you meet people who see you as “that American.” There are probably many things about Indian culture that you question, but you love the music enough to devote your life to it, and are not sure what parts of the culture are essential to the music. Consequently, if you end up in the SF Bay Area, you are likely to look for others who share your particular constellation of ambivalences, and thanks, to Gautam Tejas Ganeshan, you had a much greater chance of finding them.

Ganeshan was born in Texas to a Tamil family, and his family chose his middle name “Tejas” as a bilingual pun (“Texas” in Spanish and “light/radiance/fire” in Sanskrit.) When he founded the Sangati Center in 2006, he saw it as a return to the house concert tradition that existed before Indian music was performed in concert halls. He lived on the premises and, for a while, he even cooked dinner for every performance. The Sangati Center became one of the most important centers for Indian classical music in the SF Bay Area, eventually hosting over 300 concerts of local and international musicians.

Like many other prominent Texans, Ganeshan is often determined to stay the course once he gets an idea, regardless of the consequences. There was no amplification permitted at the Sangati Center, and important nuances were often lost, especially for vocalists. Because the musicians had no raised platform, the audience in the back rows of a well-attended performance often had trouble seeing the artist. Nevertheless, local musicians who performed regularly at the Sangati center eventually learned how to play without amplification, and some even came to prefer it. The Sangati Center made both Hindustani and Karnatik music a part of everyday life in the San Francisco Mission district. Local schools often went to concerts as field trips, and many people who had never heard of ragas began to show up regularly to see what they might discover next.

Ganeshan is on honeymoon in India, and the old Sangati Center location houses a bicycle shop these days. He assured me by email that “the Sangati Center will continue in the future, albeit in a different, more advanced form…stay tuned.” He is now doing vocal concerts in an innovative style which combines the me lodic freedom of Hindustani music with ragas ordinarily used in traditional Karnatik compositions.

lodic freedom of Hindustani music with ragas ordinarily used in traditional Karnatik compositions.

One of the most frequent performers at the Sangati Center was sitarist Srinivas Reddy. His life history shows how Raga Nerds often balance their two heritages: a progression from American music to academic South Asian studies, and then to serious commitment to Indian classical music. At an early age, he played guitar with several jazz and rock bands throughout the New England area. When he had graduated from Brown University, he was majoring in South Asian Studies and Music. When he met his guru Partha Chatterjee, he became a serious sitar student and, eventually, performer in the Maihar gharana. Despite the distance that often separates them, his guru/shishya relationship with Chatterjee has unquestionably born fruit. Reddy’s playing is lyrical and unpretentious, with a rare sense of how to make each raga tell its own musical story.

Reddy frequently travels to Chatterjee’s home in Calcutta, but also brought Chatterjee to co-teach a course on Indian music at UC Berkeley, where Reddy was a graduate instructor in the department of South Asian Studies. Today he divides his time between India, Berkeley, and Brown, performing, teaching, and promoting a greater awareness of Indian music through his Sadhana foundation.

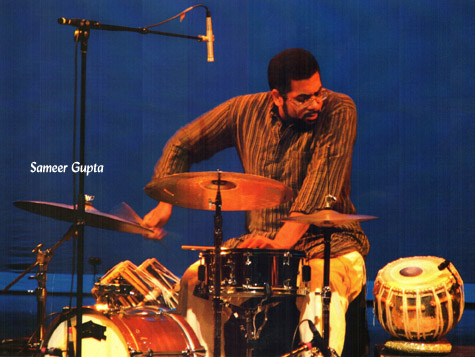

Reddy’s tabla player of choice is Sameer Gupta, who also divides his time between Calcutta and the two American Coasts. He made a name for himself as a jazz drummer, and then began to teach himself tabla. However, his first tabla teachers told him to relearn everything, and today he travels regularly to Calcutta to study with the great Anindo Chatterjee. These days it’s hard to say whether Gupta is a tabla player who plays jazz drums or a jazz drummer who plays tabla. He has played both at New York’s Lincoln Center, sometimes simultaneously. He can speak with equal authority on the major tabla gharanas and the original personnel of the Ellington Big Bands. What makes him an extraordinary drummer is the fact that he plays Indian cross rhythms on the jazz drum set in truly original ways, so perhaps it’s impossible to separate the two in his unique musical personality.

Gupta was certainly the best choice for drummer when Prasant Radhakrishnan formed his Karnatik fusion group Vidya. Unlike Reddy and Gupta, Radhakrishnan began his studies with Indian music, but on that most distinctively American instrument, the saxophone. Although he was born in the United States, he spent every childhood summer in India studying with his guru, Kadri Gopalnath, who was the first person to play Karnatik music on the saxophone. His first three albums were purely Karnatik, and the music critic of the Hindu praised him for his “strict adherence to classicism.” However, his Bachelor’s degree in Jazz performance from the University of Southern California enabled him to compose and improvise on the Vidya repertoire. Vidya included Gautam Ganeshan on violin until he decided to concentrate on singing. Today Vidya is a tight trio of saxophone, drums, and bass, which combines elements of Jazz and Karnatik music in truly unique ways.

Are these four young men the only Raga Nerds? Certainly not, but the symbiotic relationship they have had with each other and the local Indian music scene make them the easiest to write about. “Raga Nerd” may sound like an oxymoron to those Western listeners who relate to Indian music on a purely emotional level. However, anyone who is aware of the disciplined complexity and constant innovations in Hindustani and Karnatik music would fully understand why Indian “nerds” are such a powerful force in both music and computer science. The culture that produced Hindustani and Karnatik music naturally produces gifted scientists and engineers.

Teed Rockwell, a student of Ali Akbar Khan, is the first person to play Hindustani music on the Touchstyle Fretboard.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments